Today, I thought it would be fun to give some insight into how we do

native application design at GitHub. Many people are surprised to hear

the breadth of design and code that happens at GitHub on a daily basis.

We love Ruby and Rails, but we are far from a single language dev shop.

We write code in Ruby, Python, JavaScript, CoffeeScript, Objective-C,

C#, C, C++, Java, and shell of various flavors from Bash to PowerShell.

On the design side of things we obviously build web and native

applications, but we also do print,

animation and motion graphics. We design

booths, stamps, whisky glasses,

dodgeball uniforms, business cards and many

many octocats. Most of our designers work in Adobe products

but we did branch out a bit as a part of creating GitHub for Windows.

Even though we shipped GitHub for Mac almost a year before

GitHub for Windows, we've known for a long time that we wanted

to build platform-specific native applications. In fact, both

applications were conceived at the same time and share some core design

principals. They also share a lot of low level code in the form of

libgit2, but by and large they are entirely separate

entities. We specifically made the decision to write each application in

a language native to the platform, and this has turned out to be hugely

beneficial to us. Because of this separation we've been free to tackle

the problems that are most pressing for each platform and work in the

best possible tools instead of being constrained to the lowest common

denominator.

So how does an application like GitHub for Windows get built from a

design standpoint? It all starts with an idea and convincing someone

else to work on it.

Metro

In the end, Metro was my secret weapon in convincing Cameron

McEfee to work on this project with

me. Cameron was coming from a design background in print media and the

layout and typography of Metro really caught his eye. The rigid grid

system and Swiss design principals, along with a very modern and clean

feel made the prospect of designing a native GitHub client in this style

very exciting. After sharing a few sketches and some initial prototyping

work I had done, Cameron was hooked and the application started to take

shape.

Concept

Despite the existence of incredible mocking tools, I still like to start

my design work with a pencil and my notebook. Paper is still a very

powerful medium for concept work.

This is my original sketch of the dashboard in GitHub for Windows. You

can see one of my first XAML mocks kept some similar ideas.

Here is one of Cameron's first takes:

At this point, we were still discovering what is useful to display on

this view and trying to understand how this would actually be

implemented in WPF. At GitHub, we work in a very fast, iterative design

process. In this particular case, Cameron and I would trade mocks and do

design reviews dozens of times a day. We try to get design work out as

early as possible for peer review and iteration. It can initially be

intimidating to get feedback on incomplete work, but once you learn to

take things in stride it's hard to imagine working any other way.

A key part of this iterative cycle is that a single person generally

owns the design. We don't create A, B, C versions and present them

to the CEO. We don't have dedicated product managers (or managers of any

sort). Instead, we do work in small self-forming teams and those teams

generally end up naturally surfacing someone who owns the design.

The result is consistent, but opinionated design.

Just for reference, here is how the dashboard ended up in the final

release. We slowly refined our idea of Metro and began to add in more

GitHub elements while actually moving away from how applications like

Zune interpret Metro.

In the end you can see that the design is clean - living on the strict

Metro grid system and definitely focusing on content over chrome.

However, we have very specifically made this native app have some of the

feel of GitHub.com. A side-by-side perspective of the app and the

website provides an interesting example of the affinity.

XAML

One of the wonderful things about WPF applications is that you can

basically build anything that you can create in a Photoshop or

Illustrator mock-up. Cameron tended to work largely in Photoshop and I

would come in to tweak things and then re-create them in XAML (with

little or no underlying functionality). We would keep doing design as new

visual elements of the application came up. So, for instance, we didn't

actually design a progress bar until I had need of one in the

application.

As we got further along, I started committing completely to

XAML and used the Photoshop mocks merely as reference points. I tend to

work half in Blend and half in Visual Studio. If you've never used one

of the XAML designers before I have to tell you that one of my favorite

things is how you can write markup and watch the design change, or use

the color palette and watch the markup change. It is like changing HTML

and CSS on the fly in the Chrome inspector except you are actually

editing the real code and various other assets in a full fidelity editor.

Practically, this means that you can really quickly tweak colors, alignment, and even basic

components of a control without a large debug or refresh cycle. And in

the end, you check in a version-able document to your repository so that

when I change the foreground color of a text field, it is an obvious diff

on GitHub.com. Try doing that with a Photoshop document!

Styling and Templating

The other amazing thing about doing design in XAML is that you have

control over not just how your controls are styled, but also the basic

graphic components of a control. Standard buttons in WPF look like this:

But we redefined what a button looks like entirely. This can be done in

a way where buttons have to opt into the style/template, but it can also

be done in a way where you override every button. This is subtly

powerful. Here is how we define one of our buttons:

Along with doing basic graphic design, Blend also lets you do

interaction design. In Photoshop, you might have to manually lay out a

series of buttons that represent what a button looks like in the various

states of hover, pressed, normal, disabled, focused, etc. In XAML

this is natively supported through something called the VisualStateManager,

and from a design-time perspective you actually get to 'record' what

each of those states look like and then play with the behavior of the

object. You can even control how the movement between states happens by

animating properties as part of state transition.

Borderless Window

One of the most striking parts of GitHub for Windows is that it ditches

the traditional Windows chrome almost entirely. We have a small control

box for the traditional min/max/close buttons, but otherwise we killed

all the rest of the chrome. Here is how we did that.

Our borderless Window is implemented as a behavior that can be attached

to any Window in XAML like so:

<Window xmlns:win="clr-namespace:GitHub.Extensions.Windows"

xmlns:i="http://schemas.microsoft.com/expression/2010/interactivity">

<i:Interaction.Behaviors>

<win:BorderlessWindowBehavior />

</i:Interaction.Behaviors>

...

</Window>The min/restore/close buttons are just custom XAML buttons where we've

written the appropriate code to make them behave as you would expect.

The meat of the BorderlessWindowsBehavior happens in the callback where

we handle a few specific window messages to control the display of the

window. We got a lot of help and inspiration from MahApps which has a

similar BorderlessWindowBehavior.

I don't know if killing the chrome is going to be widely adopted on

Windows, but I hope that it is. For me, those 5px borders and

the massive title area on each window are simply artifacts of a past

life. They are distracting, largely unnecessary, and take up space

without providing functionality. Plus, even the standard window chrome

on to-be-released Windows 8 makes it look like your computer is 20 years

old.

This doesn't necessarily mean that every application should or needs to

be a metro application, but it has been fun to see even Visual Studio

move towards this style. I think this is very welcome change.

Vectors

We leverage vector graphics as much as possible in GitHub for Windows.

This makes the application resolution independent and makes it really

easy to move designs from Photoshop/Illustrator to WPF. For

instance, the maximize button is implemented with this path:

Performance

There was a lot of criticism in the early days of WPF about performance

and some of it was warranted in the initial versions of the framework.

These days, the tools are at your disposal to make great WPF

applications. The only major thing we've noticed is if you are running

old hardware and old operating systems (ahem, XP, I'm looking at you),

then WPF has to fall back to software rendering and this tends to be a

bit more memory and processor intensive. To the credit of the framework

we were able to release a single application that supports a huge

range of operating systems from a single code base with almost zero

platform specific code.

Some notes about performance. XAML files (an XML format) are actually

compiled down to a binary format (BAML) which makes them wicked fast to

load at runtime (sort of how nibs/xibs work on Mac/iOS). What's most important

to GUI applications is perceived performance and a responsive UI, which we achieve using Rx and making sure that we don't perform blocking operations on the UI thread.

This is the same kind of thing you have to watch out for

when writing a node application, for instance. In our case, Visual

Studio also comes with some great tools for measuring what threads are

doing work and what code is causing the UI to block (and even what code

eventually caused it to unblock).

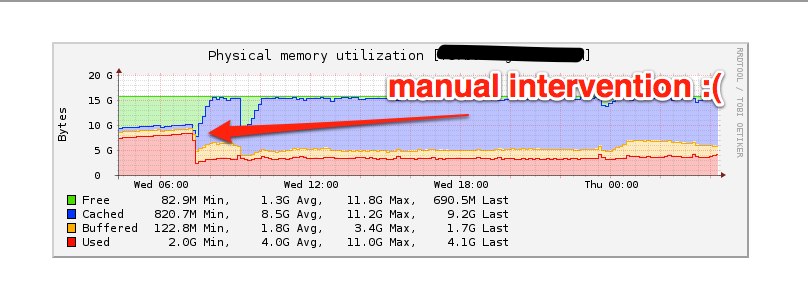

What this is showing is all the threads in my application and the state

that they are in. Generally you want that main UI thread to be green, and

all those places where you see red rectangles is where the UI thread is

waiting on another thread. When the UI thread blocks like that the

application is frozen for the user, so you want to look at what code is

running that is blocking and then what code eventually ran to unblock

the thread. If you want to use this tool yourself, make sure to follow

Paul's instructions to get real stack traces.

What you don't see

So far, we've really focused on the visual and constructional aspects of

the design, but a lot of our effort in creating GitHub for Windows went

into understanding how to make Git and the distributed collaborative

nature of GitHub accessible to people who have no desire to use a

command line tool. From a design standpoint this means we thought hard

about everything from how you download/install the application to how we

present version control concepts like making a commit or rolling back

changes. We even went so far as to package our own distribution of

msysGit and a curated command-line experience as part of the

application. Design is often most important for the things that you

don't see.